The Organic Gatorade Illusion

A new “sports drink” stands to further confuse health-conscious consumers into buying sugar water.

It will be similar to the flagship Gatorade Thirst Quencher (which used to simply be Gatorade but required clarification as the line of Gatorade products grew). The key difference in the new product is that it will be called G Organic. It will also be made with sugar from organically farmed sugarcane and carry a label whose largest word is a sprawling “ORGANIC.”

The market for products labeled “organic” has exploded in recent years, to $43.3 billion in the U.S. alone in 2015. Marketing to capitalize on that demand sometimes confusesconsumers into thinking that organically-produced products are healthier for us, a hope that has not born out. As dietician Lisa Cimperman told NPR, “I think it's a marketing ploy to apply this organic health halo to this product.”

A socially conscious cerebral cortex may be drawn to organically farmed sugar over inorganically farmed sugar, but a pancreas makes no such distinction. It releases insulin in both cases, spreading word throughout the body that this is a time of fantastic abundance. The insulin signals the body to save and pack these calories away in fat cells, for use when food is scarce. For most Americans, that scarcity never arrives. All that does is more food.

celebrities selling sugar water. (Mark Elias / AP)

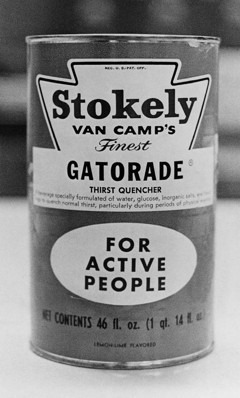

Gatorade Thirst Quencher is perennially among the best-selling sugar waters, claiming 70 percent of the “sports drink” market (which is itself a concept created by the marketing Gatorade).

Still, the sugar content in Gatorade Thirst Quencher today is much too high, and the sodium content much too low, to re-hydrate a truly dehydrated person. Properly balanced oral rehydration solutions do exist, but they don’t taste as good to most people as the much sweeter concoctions. (Last summer I tried every oral rehydration solution that’s commercially available, as well as the one that’s distributed by the World Health Organization. I get into them in detail elsewhere.)

The full ingredient list of the new product as compared to the old is:

G Organic: water, organic cane sugar, citric acid, organic natural flavor, sea salt, sodium citrate, potassium chlorideSome of the names of the trace ingredients do sound ominous—like the emulsifier sucrose acetate isobutyrate (SAIB). To test SAIB’s safety, researchers once kept a group of beagles on a diet loaded with SAIB for 12 weeks. The dogs ate SAIB to the point that their livers showed evidence of overload. I can’t recommended doing the same. But the dogs cleared the compound from their systems and came out fine. To give a product any health credit based on the absence of such compounds is distracting. Any risk they might pose in such tiny amounts is infinitesimal compared to the clear and pervasive metabolic effects of excessive sugar.

Gatorade Thirst Quencher: water, sugar, dextrose, citric acid, natural flavor, salt, sodium citrate, monopotassium phosphate, sucrose acetate isobutyerate, gum arabic, glycerol ester of rosin, acesulfame potassium, coloring agents

So the enduring rule for hydration is simple, just at odds with the messages we get from soft-drink marketing. Outside of prolonged, strenuous exercise—going a long time without getting some sugar and sodium from food—water will hydrate us. We have evolved elaborate homeostatic mechanisms to keep our electrolyte and sugar levels in balance.

Tap water, specifically—if we could become so enlightened as to be happy with it—would also skirt the environmental issue that G Organic invites by being sold only in “single-serving” 16.9-ounce bottles. Even if organic farming of sugarcane does have significant environmental benefits, single-serving bottling and global shipping has costs that stand to negate any benefit.

The single-serving approach is an attempt to give people a chance to taste the product, Gatorade general manager Brett O'Brien told Bloomberg. “There’s that misnomer that if it’s organic it can't taste good, and that’s not the case,” said O’Brien. (That’s not a misnomer, though it may be a misconception.) “We're just trying to get people familiar with the product, what it means, what it does, and try it. Once we've checked those boxes, we’ve got a big opportunity here.”

No comments:

Post a Comment