Why Warehouse Clubs Aren’t Facing an ‘Apocalyptic’ Decline

We’ve heard a lot about the retail apocalypse, and specifically, the impending doom for warehouse clubs. The story usually goes something like this: Virtually every warehouse club member has a Prime membership (this is true, as our own proprietary model indicates the number is 87 percent). So it’s just a matter of time before Amazon starts eating clubs’ proverbial “lunch.” Additionally, many club members are inviting in some lazy house guests called Alexa or Siri to shop for them. Others claim that the U.S. club business is saturated and only two club chains will ultimately survive. They point to Sam’s Club’s 63 club closures earlier this year as confirmation.

Do clubs have the capacity to compete long term with Amazon, etc.? In our opinion at HSA Consulting, yes, they do.

In fact, the club business has done quite well over the past five years. In spite of the headwinds from competitors, warehouse clubs have grown faster than overall U.S. retail sales. Apparently, consumers are happy to hold both a warehouse membership and a Prime membership.

In fact, our research confirms that they will hold both, but rarely two warehouse memberships. The food and beverage categories are doing even better, increasing annually at 4.7 percent per annum, reaching 13.3 percent U.S. share. Club share is increasing by 26 basis points each year. Factors such as SNAP reimbursement reductions, which have negatively affected the grocery industry, have had little effect on clubs.

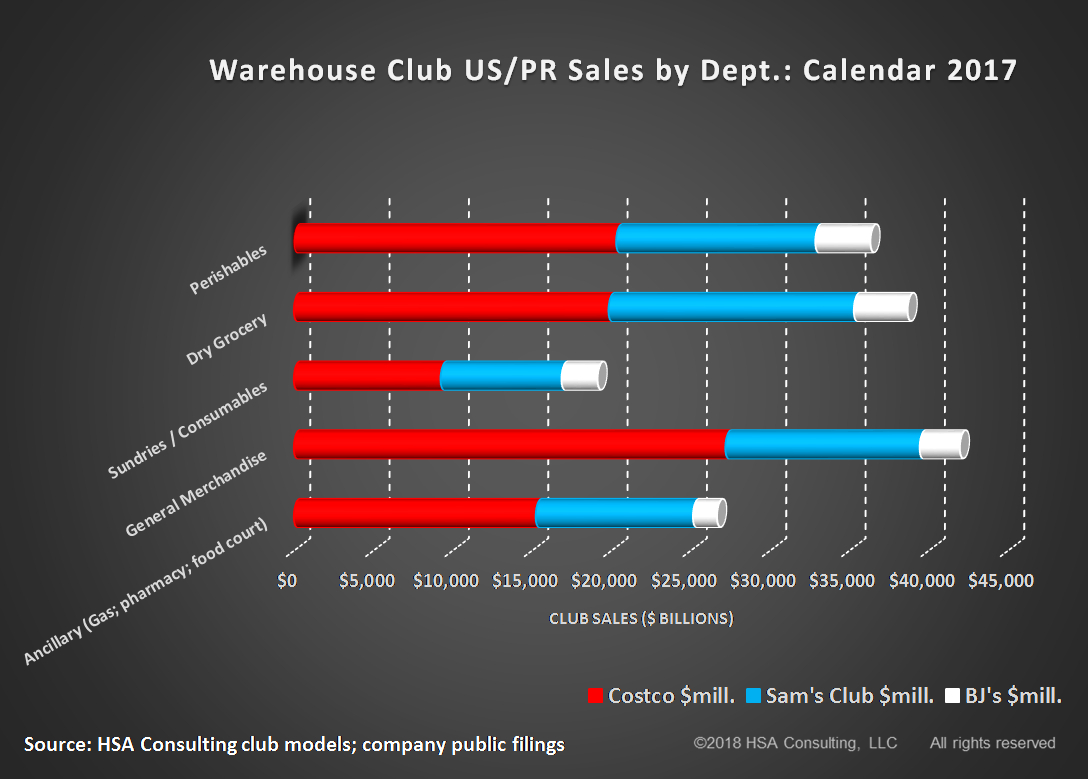

What we have seen at U.S. clubs is an increased penetration in food and sundries sales (excluding tobacco) to nearly 60 percent (total excludes membership income). This trend has stabilized over the past three years, with nonfood (including gasoline) growing 2 percent faster than food in calendar 2017.

The question remains, however: Are clubs simply more successful than grocery stores and supercenters that are also likely to lose long-term food share, or are they well placed to compete with Amazon?

HOW DO CLUBS CONTINUE TO GROW AND INCREASE FOOD SHARE EVEN WITH AN ONLINE HEADWIND?

It’s not because selection has broadened, because it hasn’t. Over the past five years, total club SKU count has declined 1 percent per annum, from 15,880 to 14,900, for the three club chains combined.

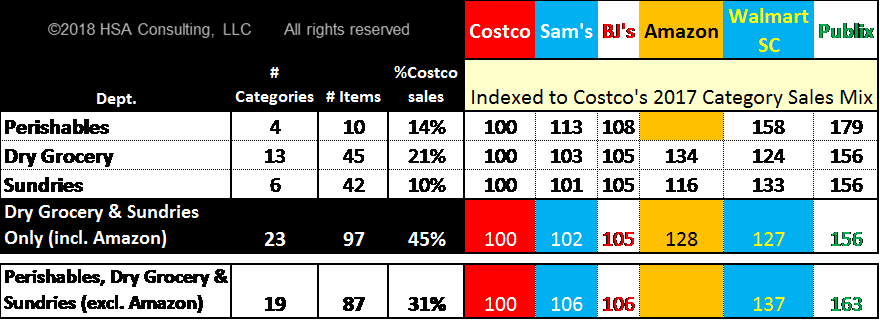

The real driver seems to be the substantial pricing advantage over major grocery chains, including Walmart and Amazon. We compared retail prices for 97 perishable, dry grocery and sundry items in 19 categories in Miami on March 1, which accounted for 45 percent of Costco’s 2017 merchandise sales. Costco was the cheapest overall, and all three club chains’ average prices were 24 percent cheaper than Walmart and Amazon, and more than 53 percent cheaper than Publix Super Markets for dry groceries and sundries. When we added perishables to the mix, the difference was even greater (directly comparable Amazon perishable items weren’t available). We recognize that club bulk-pack pricing affected these results, but while supermarket loyalty card prices were used, no allowance was made for premium club member “cash back,” which would further reduce club prices by 1 percent to 2 percent.

We also need to remember that two-thirds of Amazon’s gross merchandise value is third-party (3P) and provides little to no pricing leverage. Consolidation of Prime volume does yield last-mile cost advantages, but a shrinking portion of Amazon’s physical product sales are from owned inventory.

HOW CAN CLUBS MAINTAIN THEIR PRICE ADVANTAGE?

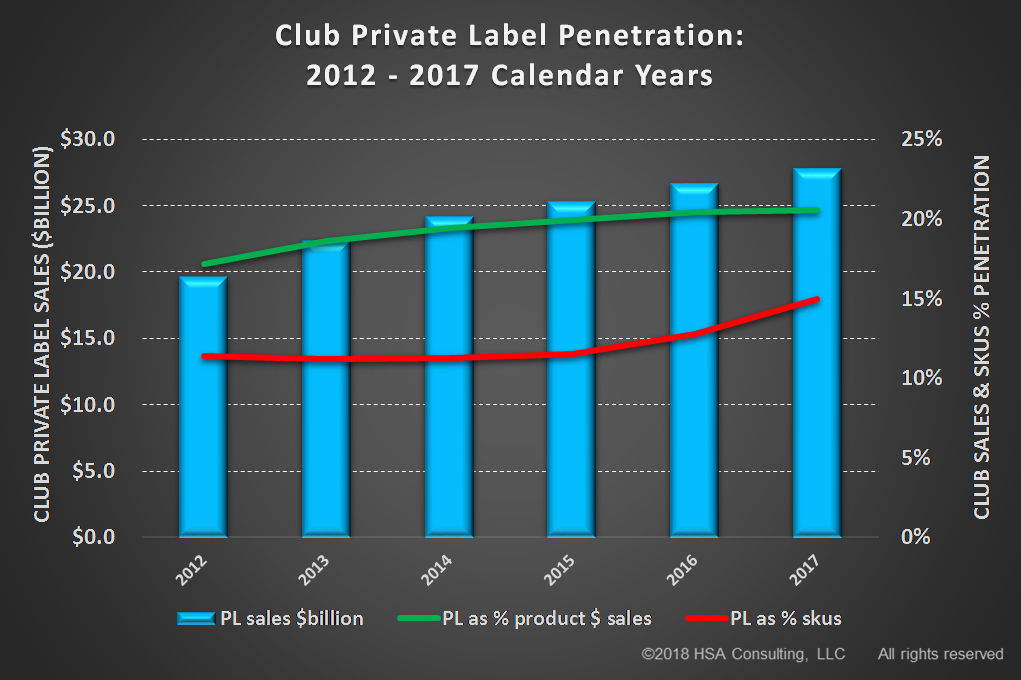

One reason that club chains have been able to maintain price advantage is their increased penetration of private label, which has grown from $20 billion to $28 billion since 2012 (7.2 percent) to 21 percent of overall club sales, and is expected to increase to 25 percent by 2022.

The second is their price advantage from a focus on reduced SKU count. This gives them two, significantly positive effects. One, it increases their pricing power with suppliers, and reduces supply chain costs. Two, it significantly reduces club operating expense, from less labor, smoother operations and inventory management as the club becomes more “pallet-driven.”

CLUBS HAVE INCREASED THEIR FOOD SHARE, BUT ARE THE SAM’S CLUB CLOSINGS AN OMEN OF THINGS TO COME?

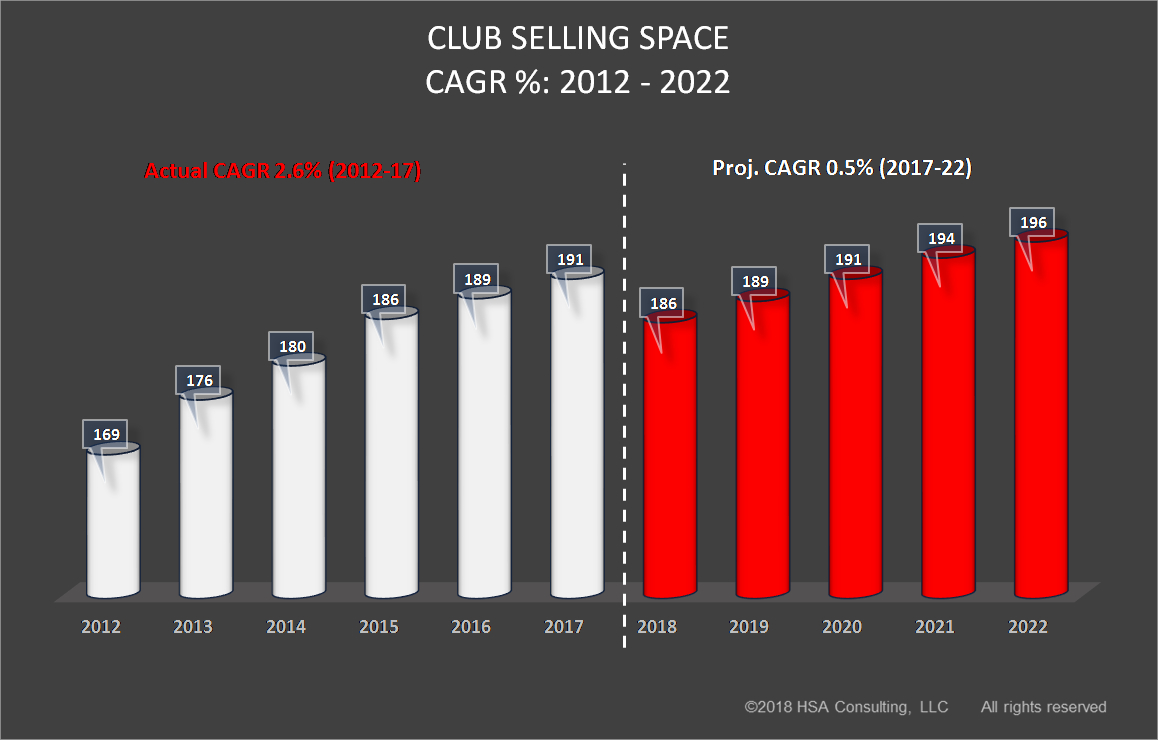

Clubs have increased U.S. gross square footage by 2.6 percent per annum for the past five years, while the grocery segment has remained flat. We project that the rate of new space additions will fall to 0.5 percent per annum, with 5 million net square footage additions by 2022 (after Sam’s 2018 closure of 7.5 million square feet). All three club chains are expected to add space, with Costco the main contributor (Costco, 44 percent; Sam’s, 43 percent; and BJ’s, 13 percent).

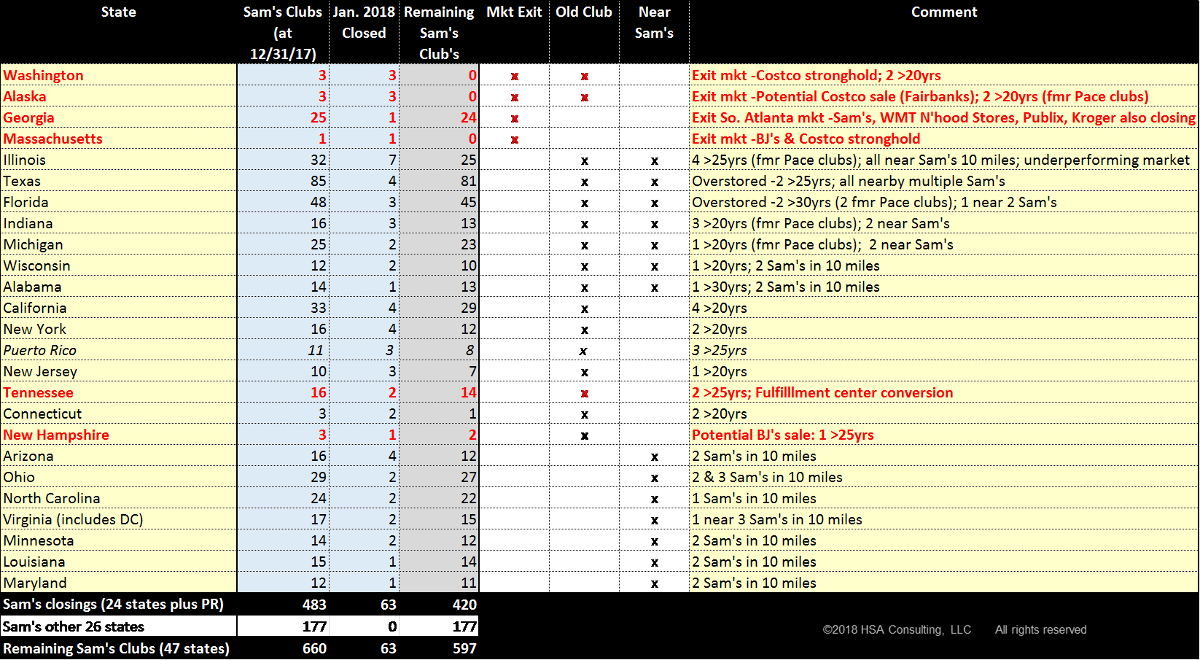

Yes, Sam’s did close 63 clubs this year. Upon further examination, 33 were 20 to 30 years old and long past their “sell-by date’ – we even helped open 12 of them in the 1990s – 27 are located within 10 miles of an existing Sam’s, which will cannibalize a portion of potential lost sales; and seven are within club competitor strongholds where Sam’s is exiting the market. The average sales of this group of clubs was half that of Sam’s U.S. average, so the maximum sales loss will only be $2.9 billion annually (before potential switch sales to another Sam’s).

For the next five years, we see a healthy tailwind for clubs if they are properly managed. We project U.S. sales increasing from $163 billion to $193 billion, and food and sundries increasing from $96 billion to $122 billion (63 percent penetration) and 15 percent to 16 percent U.S. food and beverage market share – so it’s a little premature to start writing the club obituary just yet.

No comments:

Post a Comment